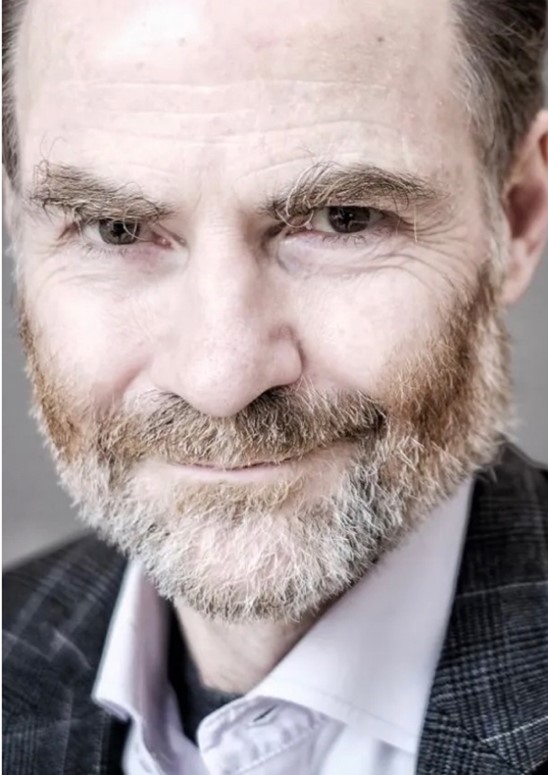

The 5th Annual Freedom Lecture Was Delivered by Timothy Garton Ash, Professor of European Studies, Oxford University and Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University

For the Fifth Annual Freedom lecture, Oxford University Professor Timothy Garton Ash examined the legacy of the 1989 Velvet Revolution and its relevance for countries in transition today. Previous speakers of the “freedom” lectures include Former Secretary of State Madeline Albright and President of the Czech Republic Vaclav Klaus.

Looking back on the fifteen-year, post-communist experience in Central and Eastern Europe, Ash noted that few would have dared to predict that the communist regimes could have been toppled as quickly and peacefully as they did. While some observers have noted that the Velvet Revolution can hardly be called a revolution, since they were not violent and did not introduce any new ideologies, Ash asserted that nevertheless, there is much to be learned from the methods used by those that initiated the political transformation. In this case, it was the means, and not the ends, that elevated the Velvet Revolution’s importance.

According to Ash, the Velvet Revolution had five basic characteristics. First, it was nonviolent. Second, it was marked by peaceful, social development, initiated from below through massive acts of civil disobedience. Third, the transition to democracy was forged through negotiations resulting from popular pressure from below. Fourth, external support influenced the success of the mass popular movements. This includes émigré groups, the infusion of information from abroad from networks such as Radio Free Europe, Deutsche Welle, and BBC Broadcasts, and pressure from the Helsinki Final Act, which demanded the protection of human rights. Fifth, there were some “slightly unsavory” tradeoffs and compromises that took place during the revolutions, including the peaceful removal of communist-era leaders from positions of power, which enabled them to retire in peace rather than in prison. Despite the lack of bloodshed, many post-communist countries experienced little transitional justice following the revolution. With no post-revolutionary catharsis, this led to frustration and a belated emphasis on the need for the lustration of communist-era leaders and sympathizers. Ash also took issue with observers who have noted that the Velvet Revolutions left no lasting legacy outside of Central and Eastern Europe. On the contrary, he stressed that eliminating the apartheid regime in South Africa was directly infused and inspired by the lessons of the Velvet Revolutions. Even in Yugoslavia and later in Serbia, the opposition throughout the 1990s to Slobodan Milosevic was marked by several characteristics of the Velvet Revolution, including moderately peaceful mass demonstrations, followed by the relatively and unexpectedly bloodless removal of Milosevic from power after free elections in 2000.

Are there countries today in which Velvet Revolutions are possible? Ash cited Nobel Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar who is playing a role similar to that played by Vaclav Havel. Opposition movements in Cuba and Iran are also adopting elements of the non-violent struggle of the 1989 revolution. Even in China, there are growing elements of the social and economic popular movements that marked the Velvet Revolution, including the growing role of civil society and the market economy. Ash regretted that in a post-9/11 world, many have tended to solely focus on the threats of terrorism and violence. This tends to blur the important fact that more people in the world today are freer than ever before. It is imperative, he stressed, that the established and great democracies of the world continue to provide a beacon for such freedom by energizing and strengthening the critical element of transatlantic cooperation between older and established democracies of North America and Western and Central Europe.